Painting by Diane Michelin

We are pleased to feature this guest blog post from Lenny Tamule. Lenny is a recent graduate of UMASS Amherst where he majored in Natural Resources Conservation with a concentration in fish ecology. Lenny also just finished up a season as a guide at Las Pampas Lodge in Argentine Patagonia. Prior to heading to Patagonia, he had an opportunity to review a recent paper on landing nets, as well as offer a personal reflection on his past use of nets.

The author Lenny Tamule admiring a stout #keepemwet fish.

It was a calm and cloudy October afternoon and that means brown trout. Within minutes, I was heading to the river. I arrived with my best bud Sully and we got right to it. We made our way down the bank in a spot that had no path. As we approached the river I saw a shadow that isn’t usually there; it was a rather large brown trout. After countless heart racing drifts, my leader stopped, and I was connected. There was a lengthy battle in a heavy rifle and fish was in the nylon net. A combination of being a broke student and new to fly fishing, a cheap, $15 net was all we could really afford at the time. The fish was too big for the small net, and its head almost stuck out. I took a quick photo (regrettably out of water) and put the fish back, but the fish wasn’t swimming and had lost the ability to keep itself upright. I nursed it and tried everything I could to get water passing through its gills but they remained shut. After some time the fish finally swam off. I was relieved. Thirty minutes later we went downstream to fish the next pool. It was then that I saw a sight that made my heart sink deep into my stomach; an upside-down mass on the bottom of the river bed. As someone who prides himself on using best practices for handling fish and getting them back to the river as soon as possible, this was devastating.

I’ve never shared this story with anyone, perhaps due to embarrassment, but I hope this story will encourage all those who read it to be as smart and kind as possible to the fish they catch (because that day I certainly wasn’t). I don’t know what caused that fish to die — was it the net not supporting it properly, or causing spinal injury, or just myself poorly handling the fish. Whatever the reason, I hope this particular study on nets as well as other catch-and-release studies can help all of us use the best release methods so that no one has to see and experience what I did that day.

Given the vast number of people who partake in catch-and-release angling, we still do not have as much science on the practice as we would like. This is especially true when it comes net types and how they impact fish health. Many people are under the impression that if the fish swims away it is healthy and ‘okay’. The reality is that we can’t always say for sure once they go back to their world and leave ours. In a study conducted by Teah Lizee and seven other scientists, they assessed the effects of various net mesh types on brook trout in, Quebec, Canada.

WHAT DID THEY DO?

Here is the skinny on the gear and methods used:

The Gear

Lightweight spinning rods.

Barbed treble hooks on size 2 spinners.

Angling took place from boat, and 5 proficient anglers were constantly rotating to avoid any potential bias in data.

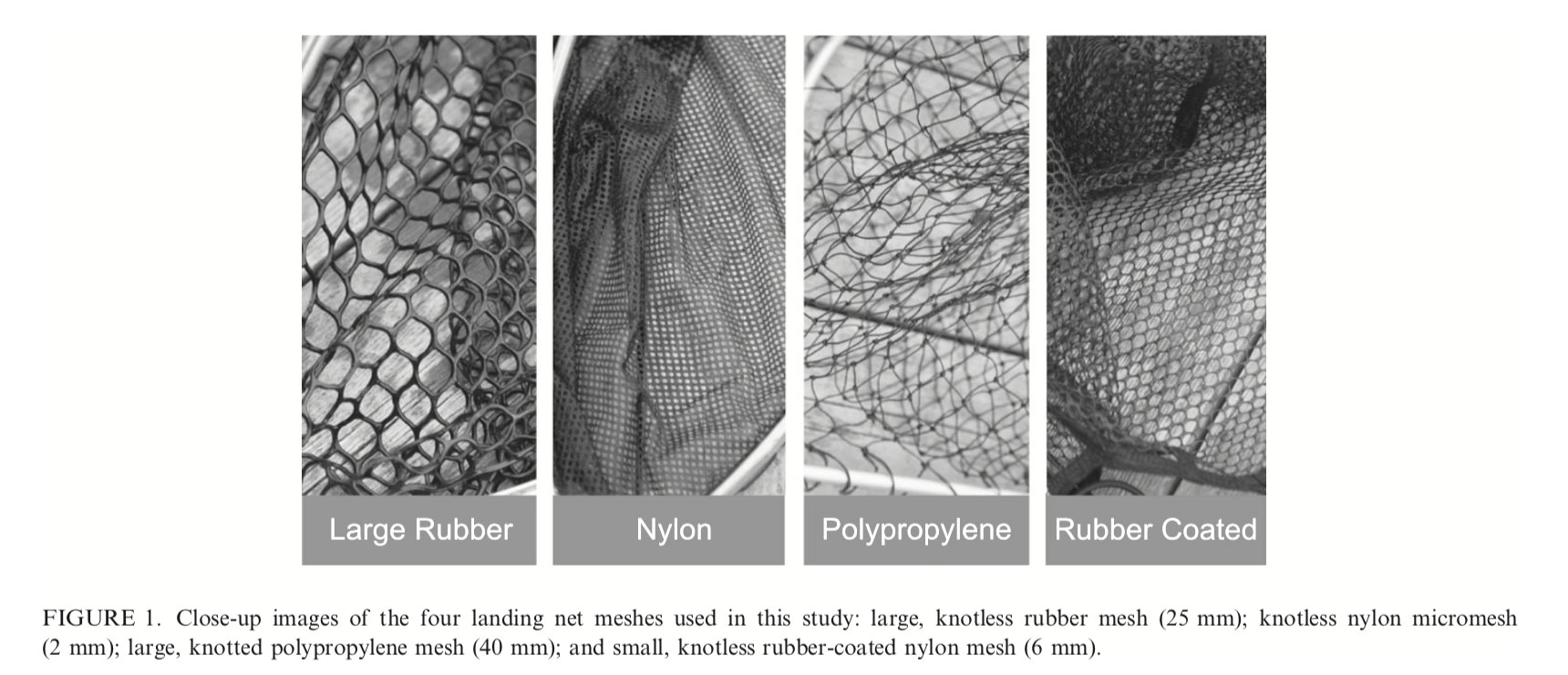

Compared large rubber mesh nets, knotless nylon mesh nets, knotted polypropylene mesh nets, rubber coated nylon mesh nets, and bare, wet hands.

Bare, wet hands were used to serve as a comparison tool for the 4 net mesh types.

From the above linked and mentioned study by Teah Lizee

The Methods

The anglers would fish and land 5 fish with each net type and then rotate to the next net type to avoid any potential bias.

Brook trout were dehooked in the boat with pliers (when necessary) and placed in a holding tank to observe any injury sustained from using the nets.

They measured mucus (slime) loss, scale loss, fin fraying, handling time, and dehooking time for each net type.

All brook trout were held in the tank for at least 1 hour for observation.

WHAT DID THEY FIND? Ranking of best to worst net types:

1. Large Rubber Mesh

Had the lowest amount of scale and mucus loss of any net type.

Caused some fin fraying (due to large mesh size that allows fins to protrude through the net).

2. Rubber Coated Nylon Mesh

Caused some mucus and scale loss.

Caused little fin fraying

3. Knotless Nylon Mesh

Caused the highest proportion of scale loss.

Caused the highest proportion of mucus loss.

Caused almost no fin fraying

Dehooking and handling times were very long because the hook frequently got caught in the mesh of the net. This is the main reason we ranked it lower than the rubber coated nylon mesh.

4. Knotted Polypropylene Mesh

Was the only mesh type found to cause significant fin fraying (5.2 times more than bare hands).

Caused little scale loss, but relatively high amounts of slime loss.

This net, the rubber coated nylon mesh net, and the large rubber mesh net all had very similar times for dehooking and handling.

5. Bare, Wet Hands

Showed high proportion of scale and slimes loss (similar to the rubber coated nylon).

Caused very little fin fraying.

Brook trout were dropped much more frequently with bare, wet hands than any net mesh type.

Dehooking and handling times were the shortest for bare, wet hands.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

Based on these results, large, rubber mesh nets are the least harmful to brook trout health, and the best available net type.

Knotted polypropylene mesh was the most harmful net type to brook trout health.

Although this study focused on brook trout, it also serves as a starting point for assessing net mesh type impacts on other salmonids as well as other species.

This study begs the question, who will manufacture a better net for fish?