by Dr. Jake Brownscombe, PhD

Research Associate, Carleton University

Keepemwet Science Ambassador

“Have a seat, Jake” the doctor said as she pulled out a small rubber mallet and proceeded to thump me on the knee with it. My leg kicked outward involuntarily. “Your nervous system is in good condition” she assured me.

If you grew up on this planet, you know the doctor was checking my knee-jerk reflex. Perhaps lesser known, the speed and intensity of this reaction can indicate internal nerve damage or the presence of disease. It’s a simple external test that indicates what is going on inside of the human body.

Fish have reflexes too. And they can tell us a lot about their internal condition, such as their level of stress, ability swim or to perceive predators. This is particularly useful for anglers because fish cannot tell us how they are feeling. If you ask a fish “If I let you go, can you swim well enough to survive?” its response will be inconclusive. Trust me, I’ve tried… more times than I’d care to admit.

The idea behind catch-and-release fishing is that the fish will survive, grow bigger to be caught again, and continue to contribute to the population. Yet, we know this isn’t always the case. Fish sometimes suffer mortality after release due to stress or injuries associated with angling (but the odds of this can be minimized substantially by using best practices - see this paper for an overview). Whether or not a fish survives depends on its condition, which can be hard to assess as an angler without any fancy medical or veterinary tools.

That is, until recent research developed a set of reflex tests that can be applied to fish, by anglers, to assess their condition. These are the four most effective reflex tests, how to do them, and what they tell you:

1. Escape response

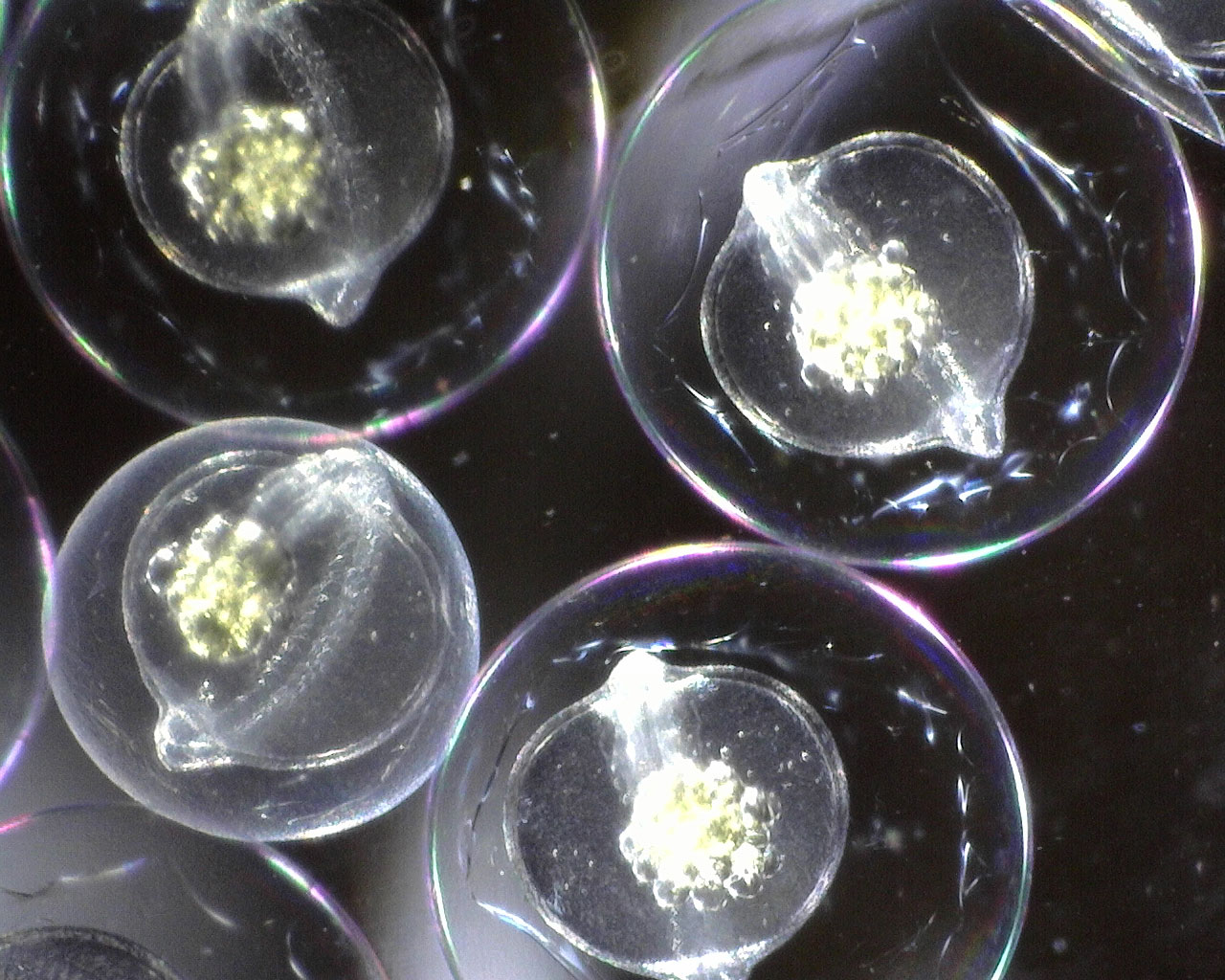

How to do it: With the fish in the water in a net or livewell (scientific holding pen shown here), approach the fish from behind and grab at its tail. Observe if the fish attempts to escape.

What it means: If a fish doesn’t try to swim away it fails this test, has at least some level of impairment and could be at risk of mortality - other tests will provide further insights.

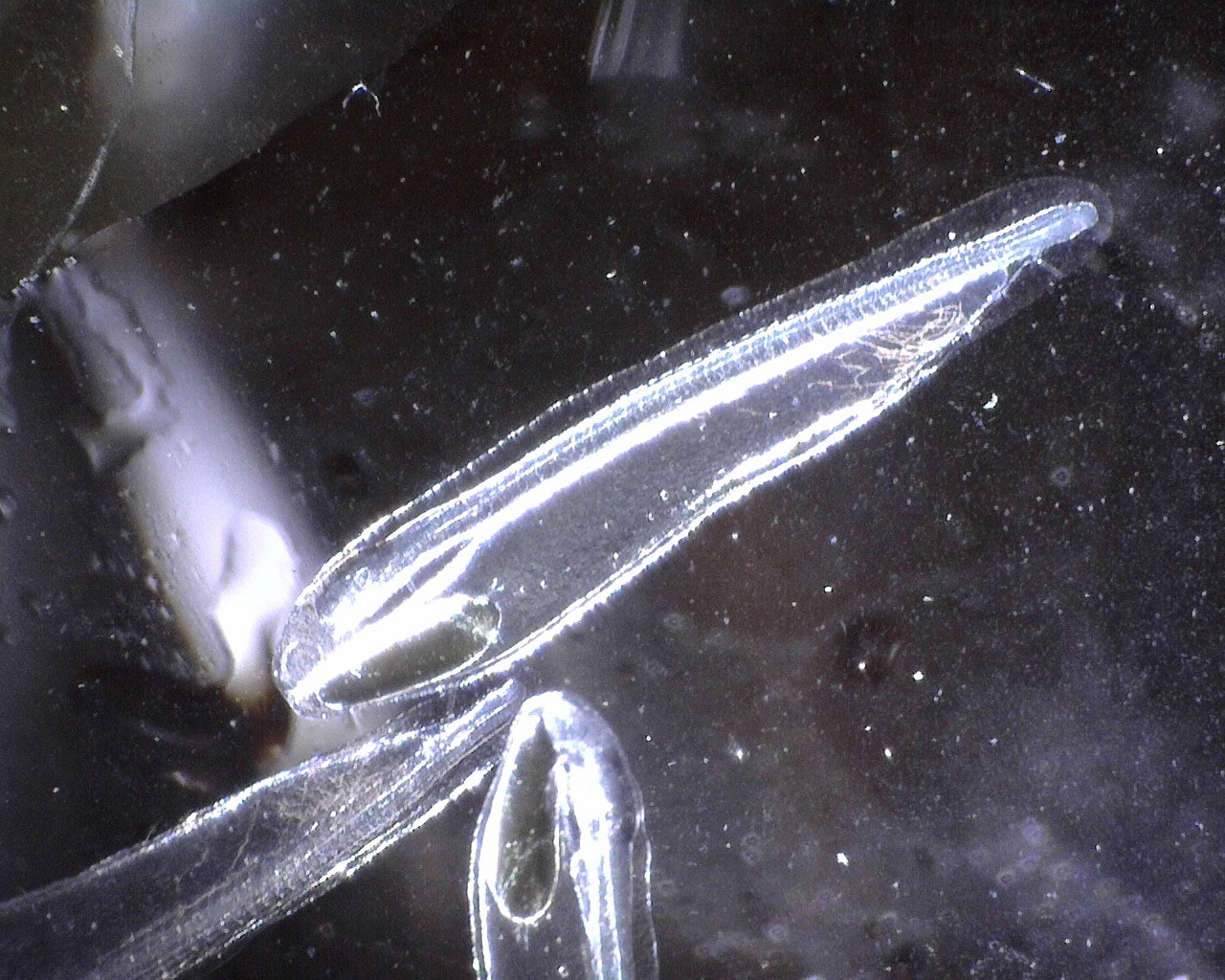

2. Righting response

How to do it: Flip the fish upside down (belly up) in the water and let go. Observe if the fish rights itself within 5 seconds.

What it means: If a fish cannot right itself within five seconds it fails this test, and is in poor condition and at risk for mortality.

Pro tip: Count the amount of time until the fish rights itself and note whether it struggled to do so. If a fish rights itself quickly and with ease, it is in good condition to swim away immediately.

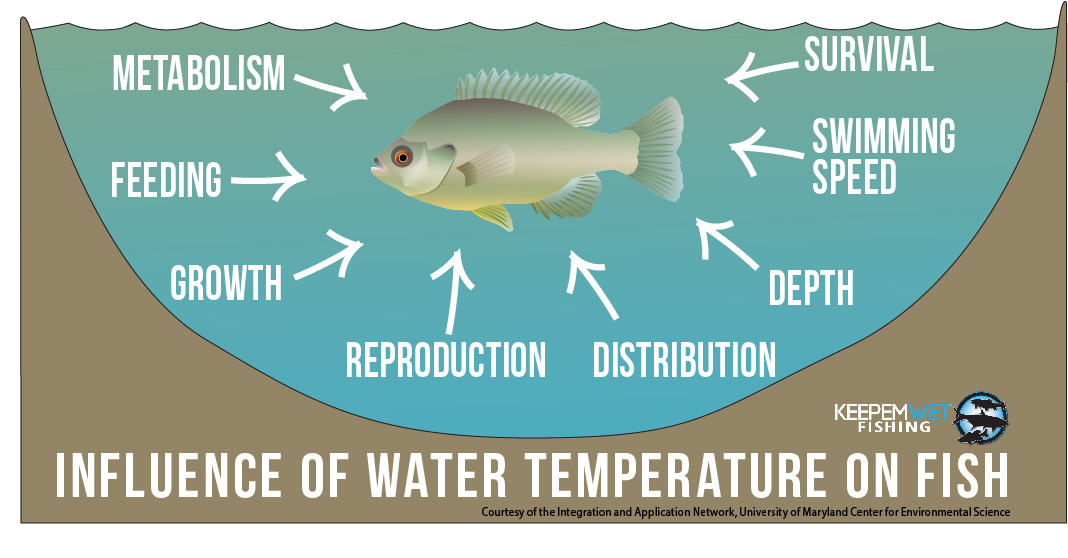

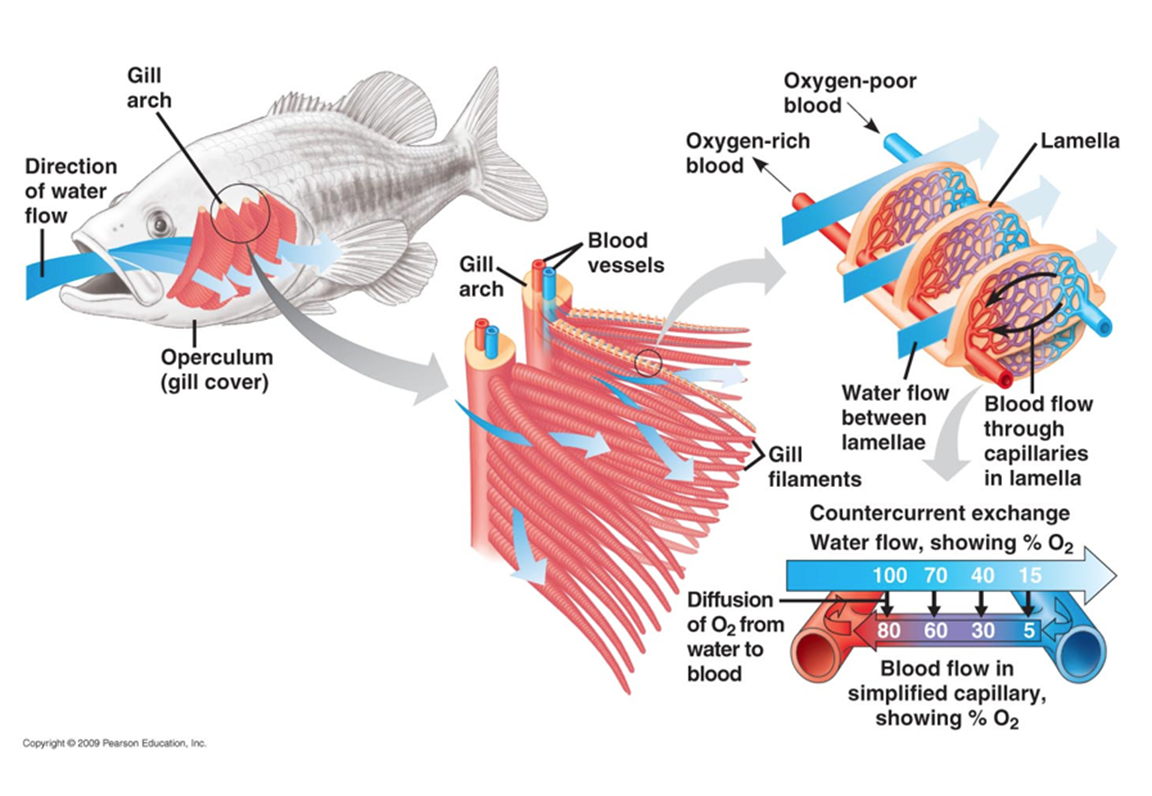

3. Regular ventilation

How to do it: Holding the fish in the water, observe for regular, consistent ventilation (opening and closing) of the operculum (gill plates).

What it means: If a fish isn’t ventilating at regular intervals, it fails this test, and is highly impaired and at high risk for mortality.

4. Eye tracking

How to do it: Holding the fish in water, roll the fish side-to-side, observing whether its eye(s) remain level (passes test), or roll with the body (fails test).

What it means: If a fish fails this test, it is highly impaired and at very high risk of mortality

While these aren’t true reflexes by strict definition, they are responses that are always present in fish unless impaired due to stress. The above tests are presented in order of operation, starting with escape response. If a fish fails this test, proceed with the righting response test, and so on. If a fish has no reflex impairment, the best course of action is to release the fish immediately to reduce handling time. However, if there is reflex impairment, particularly loss of righting response, anglers can hold fish in a net or livewell until its condition improves. Further, on any given fishing day, if captured fish are repeatedly in poor condition, anglers can consider altering their fishing practices (e.g., use different lures or fish in different locations) to minimize their impact on fish.

The Science:

The concept of using reflex tests as an indicator of fish condition was first developed and applied in the context of commercial and aboriginal seine net fisheries for Pacific salmon (see these two articles for reference) 1, 2. Based on the success of multiple studies in predicting salmon survival using reflex tests, scientists began apply these tests to recreational fisheries. This study found bonefish with impaired righting response are six times more likely to suffer predation post release (see Finsights #5). Another study later showed that reflex impairment indicates that bonefish have reduced swimming and decision-making capabilities post release, which is why they are more vulnerable to predators. Reflex tests are now used widely as measures of fish condition for diverse species such as sharks, great barracuda, largemouth bass, and fat snook. As science continues to develop the relationship between reflex tests, fish condition, and survival, these tools will become increasingly useful for anglers to assess the condition of their fish and make informed decisions about how to treat the fish prior to release.