Keepemwet Fishing and Bonefish & Tarpon Trust have teamed up to make the science that was presented at the BTT Symposium last November accessible to a wider audience. A selection of presentations have been summarized and “translated” into non-technical language that is easily understood by non-scientists. Several of the translations are below and more are available in the latest issue of the BTT journal.

What is in an angler’s control? Best practices for the catch-and-release of bonefish, tarpon, and permit

Presentation by Dr. Andy J. Danylchuk

UMass Amherst

Catch-and-release is commonly used a conservation tool for fisheries. Whether it’s mandated or voluntary, it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to know that putting fish back in the water means that there will be more fish to catch tomorrow. However, catch-and-release is only effective if most fish survive and are left with no permanent impacts. Using best practices can help anglers achieve this goal.

Best practices are actions that are often simple, and you have probably heard of many of them already, but together they have the potential to create better outcomes for fish that are caught-and-released. You can think of best practices as catch-and-release version 2.0.

Often when fisheries scientists study catch-and-release they look at the varying aspects of an angling event and how each contributes to the overall impacts of catch-and-release on an individual fish or a population. Many parts of an angling event are in the control of an angler (e.g. hook type, duration of air exposure, how a fish is handled), while others anglers have less control over (e.g. water temperature, size of the fish). The science on catch-and-release has not been conducted for all species and all aspects of angling, so while we can sometimes apply general best practices across species, it’s also important to acknowledge that species specific and location specific difference do occur.

What do we know and what do we need to know?

While there are over a dozen studies conducted on bonefish (nearly all on Albula vulpes) catch-and-release, there has only ever been one study on tarpon and none conducted on permit catch-and-release.

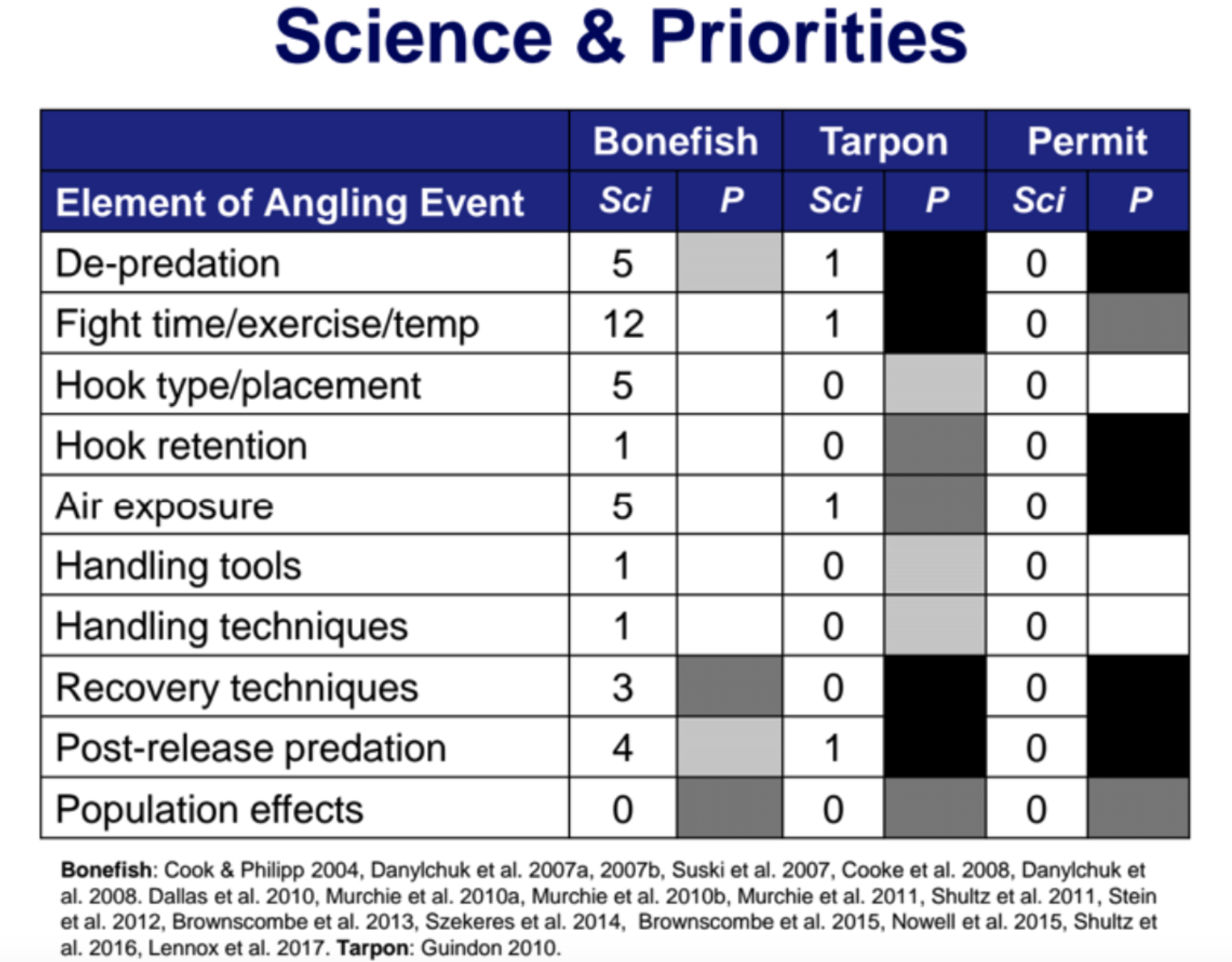

Table of the studies that have been conducted on catch-and-release (Sci) for bonefish, tarpon, and permit, elements of the angling event, and their priority for future research (P). Darker shades represent a higher priority. Some studies covered multiple elements of the angling event. De-predation refers to fish being attacked/eaten while on the line during the fight.

From these studies we are able to form some specific best practice guidelines for bonefish such as:

Bonefish that roll or nose dive (called loss of equilibrium) are six times more likely be killed by sharks or barracuda after release. Air exposure is the main cause of loss of equilibrium.

Air exposure is more detrimental to bigger bonefish and at higher water temperatures.

Multiple studies on bonefish have shown that longer handling times increase stress levels in fish and can lead to poorer outcomes after release.

Fish barbless hooks. If a bonefish is deeply hooked cut the line instead of trying to remove the hook.

Don’t use lip grippers on bonefish. A study found that they can cause significant damage.

Until more science can be done on tarpon and permit, it behooves us to use some of what we know from bonefish and other species when fishing for tarpon and permit, such as:

Reduce/eliminate air exposure

Minimize handling

Rethink the “Hero Shot”

Eventually, filling in the gaps in our understanding about how tarpon and permit respond to catch-and-release will enable us to create best practices for all flats fish.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to Ed Anderson who donated the artwork accompanying these summaries. Thank you to the presenters and their collaborators for the work that contributed to these presentations, and for allowing us to represent them in these summaries. Thank you as well to Natasha Viadero, Alora Myers, and Jordan Massie who provided assistance during the symposium.