Disclaimer:

It’s another one of those nights; quiet, cold, late and lifeless. Angry rain releases its fury onto the tin roof of my small guide cabin and wind-strewn branches scrape the thin glass window that looks out towards the vast, dense forest bordering the Dean River.

To my left, Colby snores heavily into his blanket, his whisker-clad nose and thick-furred shoulders twitching furiously as he sleeps through the storm. I smile at him; yes, it seems these nights have the same effect on us all.

The welcome flicker of a dancing flame livens up even the most ordinary of glass jars and the yellow glow illuminates the paper rested on my lap, allowing my eager pen access to the crisp white paper. I gaze at the two; so unremarkable yet so capable. The irony doesn’t escape me, and I am reminded again of why at an early age I was drawn to the comfort of such tools. As pen and paper merge, a literary intimacy begins and a message is born.

In the past I have been confined by the simplicity and politics of strict editors and conservative publications. “April, perhaps a light-hearted piece is in order? Maybe one on gear, or presentation, or even seasons…? Perhaps you can let the pot settle for a little bit before stirring it again?”

The plea is fair, for many an angler thrives on such articles, so I succumb to the unpleasant thought of stifled opinion, lingering on the edges of boredom while differentiating between dead-drifted glo-bugs and current-swung streamers.

In truth, there are only so many ways that this twenty-nine year old mind can phrase what has already been so rigorously explored and defined by men nearly three times my age.

Respectfully, I try to leave the technique-jargoned “how-to’s” for the mechanically inclined professionals — those who thrive off the vagaries of weather data, hydrometric charts and the latest and greatest in gear technology.

While relatively versed in those things, I prefer the quiet satisfaction of reader’ contemplation and the occasional bout of reflection.

I have been well behaved in my last two columns and would like to redeem my “get out of jail free” card before commencing with my next dice roll in the columnist’s game of editorial monopoly.

Defining the Grip & Grin…

The eeriness of the night has always been a cruel friend of mine. It does to me what it does to Colby, and my brain ticks and twitches with overwhelming ideas, thoughts and dreams.

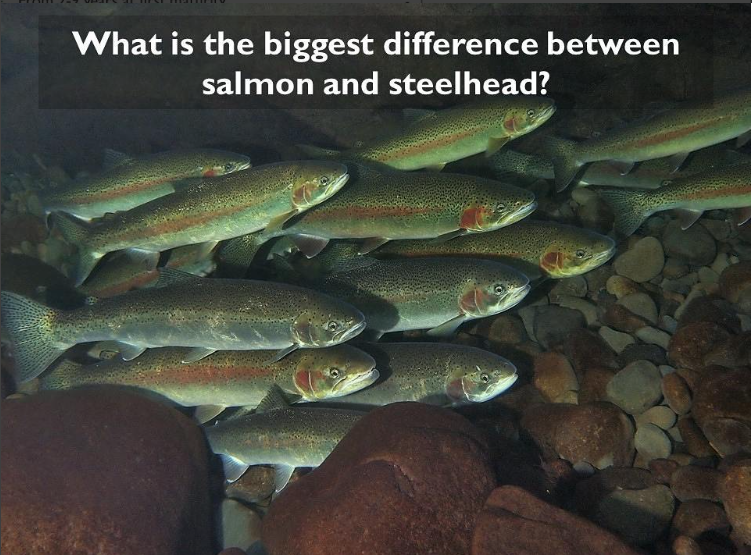

I frantically jot down my impulsive flashes and try to guide the ink across the page in the blindness of the black room. It was a night much like this nearly one year ago that was the impetus for this article. I had been lying in bed below the same tin roof, sore and satisfyingly fatigued from a long excursion upriver with fellow guide, Steve Morrow. It was the end of our season and the two of us had trekked into a long flow of water in the upper stretches of the fabled Dean River in pursuit of adventure. Steve and I had spent the last sixty consecutive days guiding other anglers and assisting them with the stalking, hooking, landing and releasing of hot steelhead that were making their migratory journey to the Dean’s tributaries.

Through wind, rain, heat and horseflies, the two of us had landed more fish than we could count and the mantra of the grip; cradle; lift; smile; click; “give her a drink;” release, made our personal fishing days all the more relaxed when it came time to land our own fish.

As an unspoken rule, if we were within talking distance we would assist each other with a speedy release, but the camera played shy, emerging only for the occasional fish thats girth extended our splayed fingers more than usual.

That night, as I lay listening to the soothing pattering of rain, I replayed the day’s events and closed my eyes to envision the metallic green and gold flecks that shone brightly around the fire in one of the wild hens’ eyes.

To do her justice there was simply no need for a camera. I saw her clear and vivid on the inner dark screen of my rested eyelids; she had made an impression on my mind and her beauty had set itself in the depths of my memory where I could visit whenever I so inclined.

I’m no stranger to participation in the classic “grip-and-grin” photo; I had the pose down to a science. Four of my fingers lightly cradle her slick, white belly while the other hand closes a firm grip around her sturdy, spotted tail. Together my hands lift on cue, allowing the light to accentuate her bright silver scales, the water droplets rolling and teetering on her soft edges before plunging back down into the river around my knees.

The fish, safe in my grasp, awaits the greedy click of the shutter, and I turn my face to the camera with a trophy smile, entranced by my jewel.

The paradox here may not be obvious at first. To be honest, I had always softly lingered on the minor contradiction that posed-photography raises. You see, for some, in that chaotic instance of camera-bag digging, electronic fumbling and verbal communication between photographer and subject, it is inevitable that a moment of pure intimacy between the angler and his prize is lost.

In a circumstance where 30 seconds is the appropriate amount of time to be shared between the “gripped” and the “grinned”, 28 of those seconds are often spent concentrating on the camera’s black dials and glass lenses, rather than on the fish.

It’s an ironic trade off; an unconscious sacrificial exchange between the moment of mental imagery and the moment of distracted, hectic poses. Both result in a stored image; one in remembrance and one in pixels.

While I most certainly will not speak for others, I eventually found myself dreading the sloshing footsteps of an encroaching photographer.

In the 30-second allotment that I had to spend with my surrendered beauty, even the smallest of distractions became an annoyance to me, and I longed to be left alone to indulge in the uninterrupted silence where my eyes could etch a permanent picture in my mind.

It might be wise for me to clarify myself further. Occasionally I wholeheartedly delight in having a remarkable steelhead documented for my photo collection. There are some photographs I desire for future reflection and gratification; an early season buck with extra-hefty shoulders, the flawless and perfectly slender doe, the dainty downturned eye above small, sharp teeth.

In such instances, whether captured by the shaky lens in my phone or by the calm fingers of a courteously hushed photographer, I’m granted my quiet moment, free of direction, poses or displaced attention. The result is ideal: mental imagery paired with captured digital images, both of which are romantic, relaxed, natural, and true.

Some of the resulting photographs focus on the most unique characteristics of the moment: the glint in an angler’s eye, the small grin of satisfaction, the blushed cheeks of both exhausted fisher and fish, the caring lift of a surrendered steelhead over a protruding rock, the splashing water from a flailing tail, each a natural marvel caught in time.

The grip-and-grin argument is not a new topic in the world of angling. In states such as Washington it is illegal to fully lift a wild steelhead out of the water before releasing it. I’m sure there are some who object to such limitations, but the argument that a fish is safer in the water weighed heavier on the conservation scale, and the law was implemented. While the science of such impacts is still controversial, it is an undeniable that if given one of two circumstances (in or out of the water), it is the circumstance of leaving the fish in the water that causes the least risk to its health.

By minimizing damage to the fish’s vital organs due to inexperienced, unpracticed handling of fish, the state of Washington justified their legislation in the eyes of many avid steelhead anglers and activists.

Whether or not I can support this regulation with scientific evidence is a moot point, but from a purely photographic perspective I find this prohibition of grip and grins quite refreshing, as some of my favourite streamside photographs are the subtle and organic shots of half submerged lateral lines, upstream-turned snouts and healthy flared gills steadied as a conscientious angler prepares a steelhead for release.